Productivity in the UK is stagnant and improving firm performance a key policy objective. Can consulting and business support programmes help achieve this objective? Despite their popularity, we still have few robust evaluations that assess the impact of these kind of programmes. Almost a decade ago, the UK government undertook an ambitious randomised control trial – the Growth Vouchers Programme (GVP) – to try to address this lack of evidence. We’ve recently published analysis of the results from this programme. This blog highlights our findings and some of the broader lessons we learned.

GVP (temporarily) increased turnover

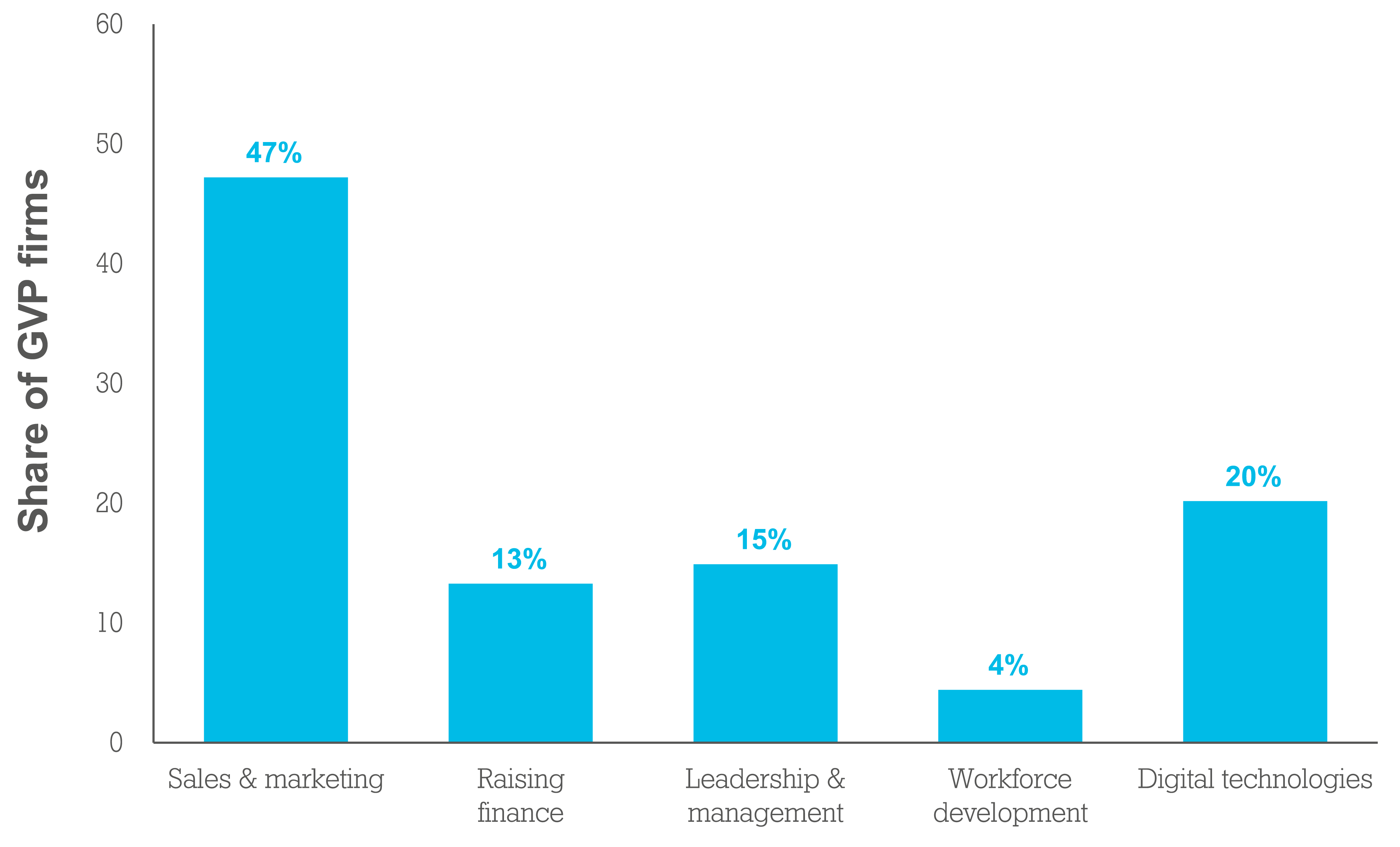

The programme aimed to encourage small and medium sized firms (SMEs) to take business advice and help them grow. More than 20,000 participants completed an online or a personal diagnostic (either face-to-face or over the phone) before selecting a theme of advice — sales and marketing, raising finance, leadership and management, workforce development, or digital technologies. As shown in the graph, most firms went for marketing – something that’s important to note given the impact we discuss below.

After selecting a theme of advice, some firms were randomly allocated a voucher to cover 50% of the costs of business advice, up to £2,000. SMEs in the control group received the diagnostic and were not offered a voucher. This randomisation of firms at large scale is what makes GVP unique.

The programme increased turnover by 8.2% among firms that received and used the voucher when compared to the control group that did not receive a voucher. However, we find no effects on employment, and the effect on turnover only lasted for a year. So, some short term benefits but no lasting effects.

Marketing mattered

A diagnostic stage can be useful to understand the most pressing needs of businesses, and signpost them to the best fit for that firm. So, it’s interesting to note that the effects on turnover are found only for firms receiving advice on ‘sales and marketing’ but not for other themes. Some care is needed here: firms selected their theme of advice – so it could be that they were already set up for faster turnover growth and this caused them to choose marketing advice (rather than the advice causing growth).

Distribution of firms by theme of advice (all firms)

Source: Does subsidising business advice improve firm performance? Evidence from a large RCT

Getting firms engaged

GVP offered the chance of free funds, but still struggled to recruit and retain businesses. A large marketing campaign in the last month of the 15-month application period helped raise awareness, and around one-third of total applications were received in the last month. There were also issues with firm participation. Only one out of three businesses given a voucher – worth up to £2,000 – ended up using it.

Overall, this low demand is in line with the evidence from other types of interventions. The voucher covered 50% of the costs, leaving 50% to be covered by the firm. And this only refers to the cost of business support – firms would also need to adopt the advice received, which requires time, resources, and capacity.

While it’s tempting to suggest that reducing the percentage of the cost covered by the firm might increase participation, it’s also important to remember that this serves as a mechanism for strengthening their commitment to the changes needed. Similar programmes need to carefully consider mechanisms for achieving both a high enrolment and a high adoption rate for the advice provided.

Increasing firm engagement

It’s not only the costs to firms that might matter for engagement – other programme features matter too. For example, a larger share of applicants dropped out if they received the personal instead of the online diagnostic. Perhaps arranging an initial face-to-face meeting or a phone call with an advisor takes more time and resources than simply completing an online questionnaire? Before jumping to the conclusion that online is best, there’s a catch – firms that received the personal diagnostic had a much higher take up if they then received a voucher. Perhaps the greater time commitment of the personal diagnostic encouraged firms to continue with the programme or it resulted in advice that felt more appropriate? Despite the lessons learned from GVP we still need to know more about the answers to these crucial questions.

From firm to local growth

Many business advice policies aim to support local or national growth, not just individual firms. GVP highlights another common lesson because most firms that used the voucher were in non-tradable sectors and medium tradable services – i.e., they tend to only serve local markets. As a result, the increase in turnover at those firms is likely to have come at the expense of other non-supported firms. This could substantively reduce the overall impacts on the local economy.

Targeting firms

Policies usually aim to target firms with growth potential. While this is ideal, it is hard to implement in practice. For GVP, the effect of using a voucher didn’t depend on the size or age of the business suggesting that targeting on those characteristics wouldn’t have made much difference on performance. However, to reduce the risk of displacement, future programmes could target exporters or firms that had potential for expanding into overseas markets (in ‘tradable sectors’ mentioned above). The Regional Selective Assistance programme provides an example.

GVP lessons

The Growth Vouchers Programme was an ambitious policy experiment that helped improve our understanding of how business advice programmes worked. As ever, we still have more to learn on this and other aspects. Robust evaluations are likely to play a key part as we keep adding to the evidence base of ‘what works’ to support firms’ performance in the UK.