Evidence review (PDF) published in July 2015.

Transport can have a positive impact on the local economy, although the role of transport in stimulating growth is not as clear-cut as assumed by many policy makers.

What is transport?

Transport includes investment in roads, rail (including light rail and subways), trams, buses, cycling and walking. Transport is essential to movement of goods to market, and people to work, study and leisure activities.

Our work on transport focuses on three types of interventions:

- Investment in expanding or improving transport infrastructure (for example, building new roads or tram systems).

- Enhancing the quality or frequency of transportation services (for example, increasing the frequency of bus services).

- Interventions which change the way transport is supplied or used, either by providing subsidies or changing the ownership and operation of services.

The rationale: How does transport deliver growth?

From a local economic growth prospective, transport investment has two main aims:

- To reduce transport costs to businesses and commuters (for example by reducing congestion – and thus saving time – or by reducing fares).

- To stimulate the economy, for example, by raising the productivity of existing firms and workers, or by attracting new firms and private sector investment.

However, the scale of economic benefits can be uncertain and there may be winners and losers locally due to displacement – i.e. firms moving closer to areas with improved connection.

Often growing economies experience transport overcrowding or congestion. Some feel that if prosperous places receive more transport improvements to address this, it will widen spatial inequalities. However, others argue that by focusing on growing areas, transport investment will contribute to agglomeration.

Transport is a public good as everyone needs to have access to transport infrastructure to participate in economy. It also has very high fixed construction costs and unknown returns, making it hard for the private sector to invest with confidence. Subsidies may also be provided to services that are not currently commercially viable.

Evidence review: What does the evidence say about transport?

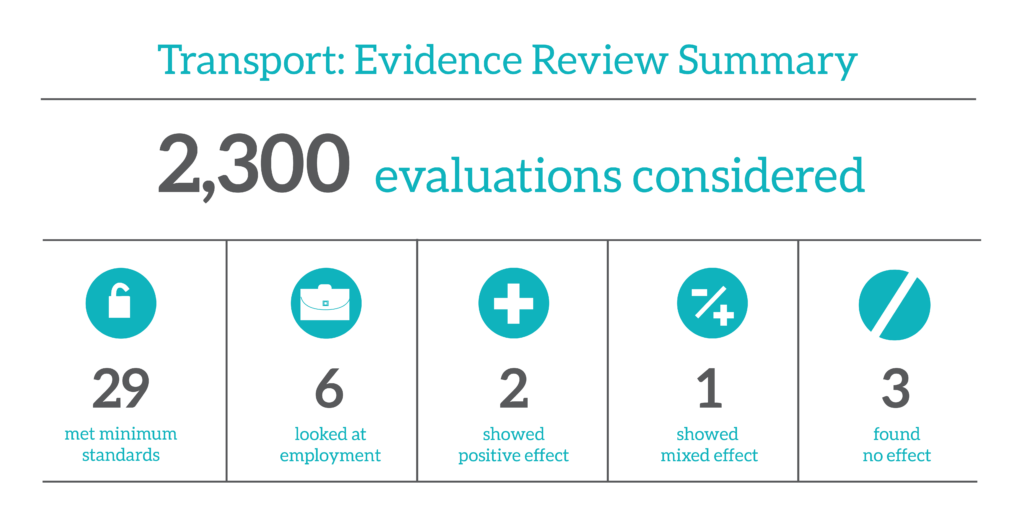

Our evidence review, published in 2015, considered more than 2,300 policy evaluations and evidence reviews from the UK and other OECD countries for a broad range of transport infrastructure. It found 29 impact evaluations that met our minimum standards.

We then conducted a more in-depth review on rail investment in 2021. This identified 29 studies, including 11 that were in the transport evidence review. The findings on roads set out below come from the 2015 evidence review, and the findings on rail are from the 2021 review.

Evidence on road investment

What the evidence showed:

- Road projects can positively impact local employment. But effects are not always positive and a majority of evaluations show no (or mixed) effects on employment

- Road projects may increase firm entry (either through new firms starting up, or existing firms relocating). However, this does not necessarily increase the overall number of businesses (since new arrivals may displace existing firms).

- Road projects tend to have a positive effect on property prices, although effects depend on distance to the project (and the effects can also vary over time).

- The impact of roads projects on the size of the local population may vary depending on whether the project is urban, suburban or rural.

- There is some evidence that road projects have positive effects on wages or incomes.

- There is some evidence that road projects have a positive effect on productivity.

Where there was lack of evidence:

- Even when studies are able to identify a positive impact on employment, the extent to which this is as a result of displacement from other nearby locations is still unresolved. More generally, the spatial scale of any employment effects varies and we do not have enough evidence to be able to generalise about the spatial distribution of effects if they occur. The same is true for other outcomes. The scale at which the studies evaluate impact varies from adjacent neighbourhoods to much larger US counties.

- Surprisingly, very few evaluations consider the impact of transport investment on productivity. Although the use of such productivity effects to calculate ‘wider economic benefits’ in transport appraisal is underpinned by a larger evidence base, it is still worrying that so few evaluations can demonstrate that these effects occur in practice.

- We have little evidence that would allow us to draw conclusions on whether large-scale projects (e.g. motorway construction) have larger economic growth impacts than spending similar amounts on a collection of small-scale projects (e.g. junction improvements).

- More generally, we do not know how differences in the nature of improvements (e.g. journey time saved or number of additional journeys) affect local economic outcomes.

- There is some evidence that context matters. For example, property price effects may depend on the type of property, while wage effects may differ between low skilled and high skilled workers. But, once again we do not have enough evidence to be able to generalise.

Evidence on rail investment

What the evidence showed:

- The impact of rail investment on employment is mixed. Some studies find positive effects, whilst others find no effects.

- In some cases, there is a positive effect on employment near the station, but this is offset by a decline in employment further away.

- Some studies find that the employment effects vary across sectors or occupations.

- There is some evidence that rail investment leads to displacement of lower-income or lower-skilled populations.

- The impact of rail investment on the number of businesses and business starts is mixed.

- Many studies find some positive findings, but there are several reasons to be cautious about these. As with employment, some studies find positive effects near the station that are offset by declines further away. Some studies looked at sectors where an impact on business numbers or starts was most likely, meaning the findings may not be more widely applicable.

- Only one study looks at impacts on business performance and productivity and finds positive effects.

- Most studies that look at the impact of rail investment on residential property prices find a positive effect; that housing prices have increased.

- The scale of the effects is highly varied, with this partly reflecting the varied time periods and geographies considered.

- Where studies look at effects over multiple distances, they find that effects decrease with distance.

- There is much more limited evidence on commercial property prices, with the only study that looked at this as a stand-alone category finding no effect.

- Only one study looks at impacts on land use and finds a small and very localised effect.

Where there was lack of evidence:

- We need more evidence from the UK of the effects on employment, number of businesses, property prices and the composition of residents.

- We also need more evidence on impacts on commercial property prices and land use and more evidence from rail networks that serve towns and smaller cities.

Overall, the impact of transport investment on employment is mixed. However, there are good reasons to invest in transport infrastructure beyond the impact on local growth.

Lessons for transport investment:

- The economic benefits of transport infrastructure spending – particularly as a mechanism for generating local economic growth – are not as clear-cut as they might seem on face value.

- Arguments for spending more in areas that are less economically successful hinge on the hope that new transport is a cost-effective way to stimulate new economic activity. We do not yet have clear and definitive evidence to support that claim.

- Our findings raise fundamental questions about scheme appraisal and prioritisation, and about the role of impact evaluation in improving decision-making around transport investment.

Lessons for rail investment:

- Policymakers should be realistic about the likely employment and business impacts of rail investment. While some studies find that new and extended rail lines increase employment and the number of businesses in the areas around new stations, others find no effect.

- Policymakers should be aware that employment impacts are likely to occur close to stations and possibly come at the expense of other areas nearby. Findings are similar for businesses.

- Policymakers should consider current and future housing supply to understand the potential impact of any rail investment on local property prices.

- Policymakers should carefully consider and monitor the impact of rail investment on local communities. Some studies suggest investment may lead to lower-skilled or lower-income households being displaced.

Downloads:

Toolkits: Advice on designing transport programmes

In addition to the transport evidence review and the rail investment rapid evidence review, we have two policy design toolkits to help policy makers make informed decisions. Each toolkit covers a specific type of investment. The toolkits consider a broader evidence base than the evidence review.

Case study: Advice on how to evaluate transport programmes

One of the main challenges in evaluating transport investment is that the use of cost-benefit analysis means that much infrastructure spending occurs in areas where there is expected to be strong and growing demand. Often these locations will already be experiencing economic growth and increases in jobs and wages. The effects of these underlying factors (‘selection effects’) must be accounted for if we want to understand the extent to which transport spending increases growth. For this reason, treated areas are almost always likely to be different to untreated areas. Some of these differences will be hard to observe in available data, making it very difficult to construct an appropriate control group. An additional complication is that these underlying differences are unlikely to be constant over time

To help improve evaluation of transport programme, we have a case study that gives an example of how a previous investments have been evaluated. Each What Works Growth evaluation case study has met our minimum standard of evidence, which means it (at a minimum) compares what changed for the places, businesses or individuals that benefited from an intervention with what changed over the same time frame for otherwise comparable places, businesses or individuals that didn’t benefit, or that received a different type of intervention. This study uses a statistical approach, using the fact that some firms benefit from improved access because they happen to be close to road projects. They compare the changes in nearby firms’ economic outcomes before and after the new roads opened with changes for firms further away. This technique is called an instrumental variable approach, which is scored 4 on the Maryland Scientific Methods Scale.

Other resources

We conducted a brief review on the impact of congestion charging policies. We found a total of 12 studies that met our inclusion criteria.

Overall, there is evidence that congestion charges reduce congestion and can reduce air pollution. There is also evidence that it may decrease retail property values and increase housing values. Policymakers should ensure that there are public-transport alternatives for the congestion charge to work. This public transport infrastructure can be funded through the congestion charge.