This blog was originally published for the Local Policy Innovation Partnership (LPIP) Hub. The LPIP Hub seeks to address nationwide issues through local partnership and place. It is a national consortium, led by City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Here are some common scenarios in local authorities:

- An officer has a week to finish writing a bid, which also includes a cabinet member briefing, arranging SRO signatures, and reviewing the latest version of the budget from finance, amongst other tasks. In the last push, they ask a colleague to fill in the blanks in the rationale for the project. “Wherever you see ‘X’, could you figure out what that number should be?”

- A project manager has taken on delivery of a project that someone else developed. The quarterly targets look reasonable, until they realise that it’s based on two full years of delivery. It’s going to take six months to get the project up and running—which means the targets for the remaining quarters are likely unachievable.

- The Economic Development Manager is leading on a joint bid with other departments and partners. Now that everyone has chipped in, however, the list of project objectives looks suspiciously like all of the corporate priorities. It feels as though the project might be spread too thinly to achieve any of them.

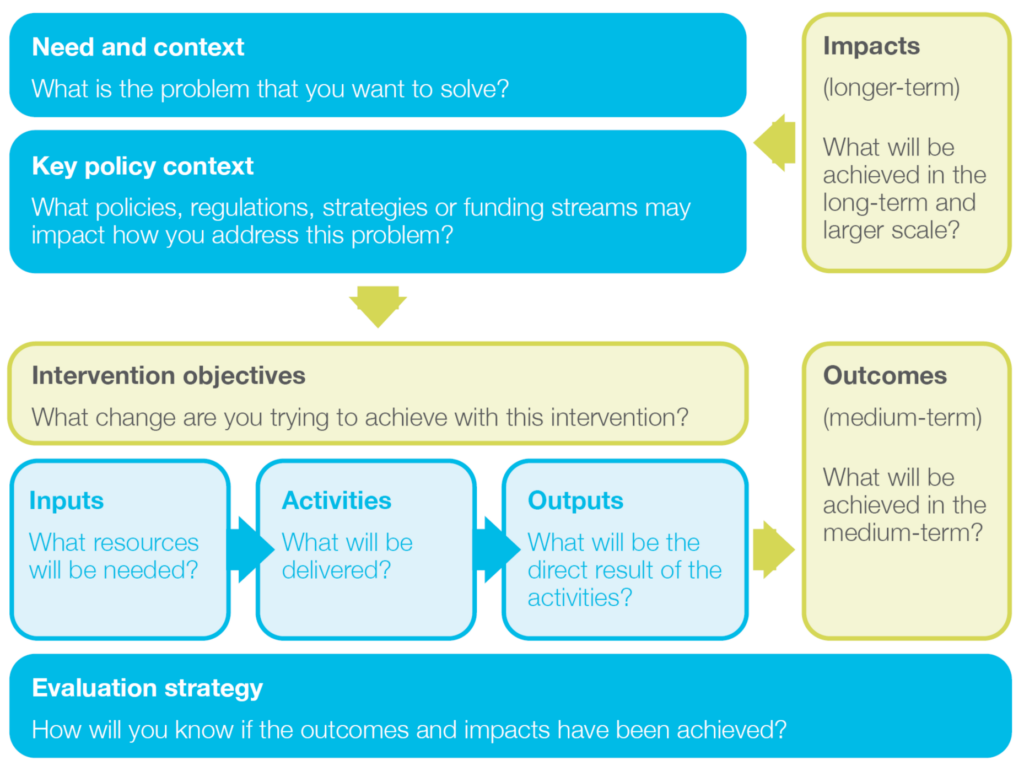

The people in the scenarios above could likely all benefit from developing, or refining, a logic model. Logic models set out where you are (the need and context), where you want to go (the impacts and outcomes), and how you’re going to get there (the inputs, activities, and outputs). Below is one example taken from our guide Using logic models, but there are many other layouts to be found online. Brevity, however, is a key requirement.

Figure 1:

Checking the logic behind your project

Structuring your project around these prompts isn’t, in itself, anything special–most planning tools will include a variation of these. However, the real strength of logic models happens in checking the logic between each step.

Logic models remind you that there should be strong evidence behind the need—don’t jump to the activities to be delivered and then fill in the evidence afterwards. And that need for evidence feeds through the process as part of testing the logic between steps—there should be strong reasons why these activities have been chosen and not others.

Looking for assumptions

Probing the logic between steps also helps to highlight assumptions that have been made—about recruitment of participants, completion rates, availability of staff time, or that a project will start from day one. Often in-kind support from partners is assumed rather than spelled out; which will often have an impact on the activities, timelines, and even what impacts partners expect from participating in a project.

Managing expectations

A logic model can also help to manage expectations of whether the activities will change the outcomes and impacts listed, and whether that change will be measurable. Hundreds, if not thousands, of projects being run across the country right now state that they will lead to an improvement in area GVA, but in most instances that can’t be attributed to one project. Being clear with partners and senior decision makers about what outcomes can be achieved, and which can’t, is critical.

Providing clarity, even in complex systems

Some worry that the logic model is too simplistic because projects, and the problems they are trying to address, are complex. However, they can be used alongside systems mapping or other processes, using a logic model to get clarity on specific elements within the system. In particular, logic models are useful when discussing projects with colleagues and stakeholders. By simplifying the project, it highlights the key reasons for the activities—the need and addressing that need.

Focus on the process, not the template

And it’s a flexible tool. Recently we’ve had feedback from an umbrella organisation who found it useful to clarify their pitch to government—being clear about what they do, and don’t, offer. And someone from a government agency told us that they’d used it to ensure that sustainability was a golden thread through their projects.

In our training and guide on using logic models, we focus on the process rather than the diagram. A logic model isn’t a template to be filled in and put to one side. It’s a useful tool to support discussion when collaborating on project design, when thinking through likely outcomes, and when communicating the project to others. It provides a useful reminder to be clear on the problem long before jumping to solutions, and to be realistic about the outcomes.

More information, such as reviews on the evidence of local growth policy, details on training, and further support on using logic models can be found at the What Works Growth website. Additionally, you can subscribe to the What Works Growth newsletter.